“Why do farmers farm, given their economic adversities on top of the many frustrations and difficulties normal to farming? And always the answer is: "Love. They must do it for love." Farmers farm for the love of farming. They love to watch and nurture the growth of plants. They love to live in the presence of animals. They love to work outdoors. They love the weather, maybe even when it is making them miserable. They love to live where they work and to work where they live. If the scale of their farming is small enough, they like to work in the company of their children and with the help of their children. They love the measure of independence that farm life can still provide. I have an idea that a lot of farmers have gone to a lot of trouble merely to be self-employed to live at least a part of their lives without a boss.”

― Wendell Berry, Bringing it to the Table: On Farming and Food

While iFarmer fosters the vision to construct Bangladesh’s most efficient and largest agri-financing and supply chain platform by improving the livelihoods of the farmers who are our key stakeholders, we - the Impact team at iFarmer are on a constant pursuit to understand the complexities of the farmers’ lives. We want to know what it is like to be a farmer in a land known to be one of the most fertile lands on planet Earth. A land of which over 70% is arable i.e., able to support farming and crops. It is the great fertility of the land and its warm, well-watered climate that continually attracts people, even after devastating floods and cyclones have wrought such great devastation over the years. To the 16.5 million farmers across Bangladesh, one of the world’s poorest and densely populated countries, the risks of farming are worth taking. But why and for how long?

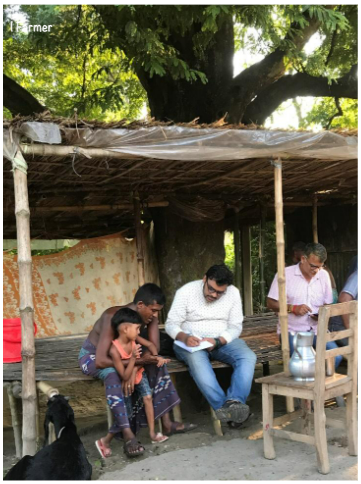

The Impact team delved into a 3 months long Ethnographic Research Study across 4 districts to understand our farmers better - experience a day of their lives along with them, identify their behavioral patterns and learn more about their evolving pain points. When we were designing the research study, truth be told, we were not sure how this will benefit us or how we can steer this study to identify what we need to know. The brief I gave to my team was quite simple – “We talk about their pain points that we are trying to address; we work with the solutions we think they need. But who are these people? What drives them to do what they do? Are they happy being farmers? What troubles them enough to keep them up at night? What drags them out of the bed every morning despite knowing they have the most difficult day ahead? If our core work is to measure, evaluate and assess the impact we as an organization are having on these people, we should start by really understanding them. Let’s go and find out who our farmers are.”

Ethnographic research focuses on problems that are identified as important by both the researcher and key people of the research location. The process involves longer term face-to-face interactions with people in the research community. For our study, we set four primary objectives:

- To monitor whether farmers are receiving timely service and assess the effectiveness of all iFarmer services.

- To collect unfiltered feedback from farmers - to evaluate that our services are aligned with farmers’ major current pain points.

- To identify further categorization of farmers (farming experience, environmental drawbacks of their location, farmers who practice agriculture as a secondary occupation, farmers who are relatively wealthier, veteran farmers, young farmers, novice farmers etc.) and qualitatively assess their needs.

- To experience their struggles, decision making processes and their day-to-day activities first-hand, by shadowing or following them for a particular period of time.

This multimethod study was conducted through questionnaire surveys, in-depth interviews, key informant interviews, focus group discussions and context immersion. Our team of 4 members visited Nilphamari, Jashore, Natore and Joypurhat over a period of three months.

Our study reflected the changing needs of farmers and significantly contrasting behavioral patterns, across different districts. While farmers in Nilphamari have almost always been dependent on availing financing and loans, the farmers of Jashore are involved in running small businesses which are mostly their primary income source. Similarly, the farmers at Nilphamari were seen to have a tendency to purchase cattle with their profit and/or savings after each cropping cycle, hoping to earn money from its sale in times of crisis or large losses. Whereas, the farmers we spoke to in Jashore immediately reinvested their savings/profit in their next cropping cycle or in their other businesses. On the other hand, speaking to the female farmers at Natore was a surprising delight for our team. Contrary to the traditional mindset and social norms, the women farmers we had the chance to speak to were either the sole decision makers or played an active role in household decision making along with her husband. During an in-depth interview, Aparna Rani, a vegetable farmer from Araji Maria village in Natore beamingly said, “My husband hands over all the cash to me every month. I spend it accordingly and allocate a portion for him whenever he needs.” Every month, Aparna is also able to keep some savings for herself which she mostly spends on buying toys for her twins and other household necessities. A stark difference was seen in Joypurhat where even though the women farmers are rearing the livestock within her residence, tending to it from the moment of purchase – she has very insignificant to zero control over how the money from the sale of the livestock is spent. This was an indication of how it is frowned upon for the women to be involved in the selling process which requires her to visit the local marketplaces or “haat”.

While we work on the development of the final report based on this Ethnographic Research Study, my team and I often end up discussing snippets of conversations we had the privilege of having with our farmers. Throughout the last three months, we met people like Abdus Sattar from Nilphamari, who began with an inherited land of 310 decimals, fell under a vicious cycle of loans when trying to cultivate in the land and had his fruit shop demolished to dust due to conflicts. At 57 today, he owns 372 decimal sized land where he is cultivating potato and corn, married off his eldest daughter, has his son pursuing a Computer Engineering degree, and his daughter enrolled for Higher Secondary School Certification. He said he needed the struggle to work twice as hard and get to where he is today, because he is finally content with his life. We met Alo Rani from Natore, who lost her eldest son followed by which her husband passed away, leaving her with their land in mortgage, pending hospital bills of nearly 7 lacs and a toddler. Fast forward to today, Alo Rani’s son is halfway through his HSC exams. Together with her son, she is planning to expand her farming and make a lychee garden beside her house. Her neighbors see her grit and perseverance, reminding her, “There is only one Alo Rani in a million.”

This was an experience of a lifetime for me. Being right next to them when they are making decisions that eventually trickles down to bringing food to our tables, being in the moment when their eyes swell up while telling their story and watching them break into a smile when they tell us how they held their heads high and turned their story around. As the Canadian poet Brian Brett once said, “Farming is a profession of hope.” Lucky are the ones like us, who can get glimpses of how they keep this hope alive and more often than sometimes, we can even reignite the hope. For ourselves and for our farmers.

০১৩০২৫৩৬০২৬

০১৭৮৪১৬৭৯৭৩